Archives Southasia: Creating, Curating, Connecting

- Home

- Post right sidebar

- 19 July 2012

- By admin

- 0 Comments

July 28-29 2012

Laxmi Murthy

“An archive is o nly as good as those who manage it,” said historian Ramachandra Guha in his opening remarks at a recent meeting organised by the Hri Institute in Bangalore. Lamenting the decline of public archives in India, Guha highlighted the sterling efforts of the early directors of the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, such as B R Nanda and Ravinder Kumar, along with their dedicated teams. In its heyday in the 1980s and 90s, immaculately preserved and catalogued primary sources led to the NMML being the source of most of the innovative and rigorous work on modern Indian history. The apathy that contributed to its stagnation can be sharply contrasted with the passion with which deputy director Haridev Sharma braved bureaucratic hurdles, foreign currency regulations and sanctions during the apartheid regime to source – via a like-minded American scholar – records from South Africa to add to the documentation on MK Gandhi’s early life in that country. With the NMML once more being headed by a historian, scholars can hope that the institution can be invigorated.

nly as good as those who manage it,” said historian Ramachandra Guha in his opening remarks at a recent meeting organised by the Hri Institute in Bangalore. Lamenting the decline of public archives in India, Guha highlighted the sterling efforts of the early directors of the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, such as B R Nanda and Ravinder Kumar, along with their dedicated teams. In its heyday in the 1980s and 90s, immaculately preserved and catalogued primary sources led to the NMML being the source of most of the innovative and rigorous work on modern Indian history. The apathy that contributed to its stagnation can be sharply contrasted with the passion with which deputy director Haridev Sharma braved bureaucratic hurdles, foreign currency regulations and sanctions during the apartheid regime to source – via a like-minded American scholar – records from South Africa to add to the documentation on MK Gandhi’s early life in that country. With the NMML once more being headed by a historian, scholars can hope that the institution can be invigorated.

In sharp contrast to the dismal state of public archives is the vibrant Panjab Digital Library (PDL), started, as executive director Davinder Pal Singh recounts, by “a group of enthusiastic youth with a 3.1 megapixel camera, a desktop computer, a car and a vision”. Since its launch in 2002, PDL has digitized more than seven million pages and uploaded more than a million. Davinder spoke with immense sadness about what he termed “libricide” or the deliberate destruction of libraries in the 20th century, by the Nazi army between 1932 and ‘42, the burning down of the Jaffna Public Library in 1981; the Sikh Reference Library in 1984; destruction of libraries in Iraq by the NATO forces; and the destruction of the National Library in Sarajevo by the Serbs, in the attempt to obliterat e chunks of history.

e chunks of history.

Even as historian Indira Chowdhury urged participants to view “memory as history”, she spoke about the challenges of archiving oral history. Using the contemporary examples of Nandigram and Singur in West Bengal, which witnessed violent struggles over land acquisition for industry, she shared her documentation of folk art, both visual and oral. Her thoughtful question, “How do levels of intimacy and pain that belong to the realm of experience shape oral narratives?” lingered long after the haunting notes of the folk musicians of Nandigram had receded.

What makes history? No longer is history conceived of as dusty manuscripts and texts alone. Family photographs are rich repositories of the histories, not only of that particular family, but also of that social milieu. Anusha Yadav, founder of the Indian Memory Project, motivated to delve into her own ancestry through family photographs, encountered an overwhelming response to her initiative that began as a Facebook page. The need to retrieve the past, more acute among the diaspora, has contributed to the expansion of her project to also include letters. The powerful pull of reaching back to family history is echoed by Nayantara Gurung Kakshapati, co-founder of the Nepal Picture Library, whose “Retelling histories” has touched a chord in many youngsters eager to know more about where they came from. The posed studio portrait, the solemn family picture taken on special occasions, as well as candid shots, tell diverse stories.

As stories go, Mofidul Hoque, founder of the Liberation War Museum in Dhaka shared the process of collating what he termed “magical moments” from family histories. As part of the documentation of narratives of Bangladesh’s Liberation War in 1971, a veritable “mobile museum” travels around the country, encouraging students to record narratives from their family. Not only does this aid in building localised histories, it also takes the stories back to the communities in the shape of booklets, with the names of those who have shared their personal memories, thus contributing to building history.

On the western edge of the Subcontinent, Haroon Khalid, writer and Hri researcher described efforts to collate oral narratives of Pakistanis’ experience of the ’71 War. Exhibitions of testimonies, photographs and letters from that time made the war on the eastern front come closer home. Primary sources and myriad realities could enable youth to come to their own conclusions about the war.

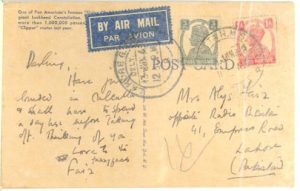

Legacies of Partition come in a myriad forms. Salima Hashmi, artist and Dean of the Beaconhouse National University in Lahore, brought alive the tumultuous times of post-Partition Pakistan during the 1950s, when her father Faiz Ahmed Faiz, along with several others, was jailed in what came to be known as the “Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case”, for plotting to overthrow the government. Despite censorship, letters to his wife Alys, severely damaged by insects and humidity, nevertheless provide amazing detail of life in the jail, as well as contemporary politics, through the radio and other sources. A particularly poignant letter with a poetic description of the sunset ends on a wry note, “…perhaps I might even become a poet”. The letters, original works and other memorabilia, preserved in Faiz Ghar, allow the public a glimpse into the life and times of one of the foremost poets and journalists of his time.

(Courtesy: Faiz Ghar)

The role of individuals in preserving history and creating intellectual space cannot be underestimated, as Geoffrey Myint, Hri researcher and anthropologist based in Yangon reminded us. The Ludu Library, set up as a tribute to two of Burma’s foremost intellectuals Ludu U Hla, and Ludu Daw Amar, houses one of the country’s finest collections of material on labour issues. U Hla’s passionate belief that public discourse should be accessible and comprehensible to the masses is his priceless legacy as Burma attempts to rebuild its history after decades of military rule. Kanak Mani Dixit, editor of Himal, brought up the contentious issue of funding. As Burma opens up, he pointed out, donor aid pouring in could possibly be channelled to the important task of rebuilding archives.

Access is perhaps one of the most crucial aspects of archiving, as Amar Gurung, director of the Madan Puraskar Pustakalaya, Kathmandu, adds. Having spent the past few months at the National Archives in Delhi attempting to map the material on Nepal, Gurung has launched an immense appraisal process of not only what exists, but how to access it. Future scholars of Nepal will be indebted to him for this painstaking work, not least because an archive can also function as an arbiter. What is preserved and what is not? What is accessible, and to whom?

Abhijit Bhattacharya, recalling the twenty-year experience of the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Kolkata, in rescuing endangered archives and housing them in a safe space, points out that the process of selection is what determines the character of the archive. Criteria like budgets are doubtless important, but within institutional frameworks, an overall ideology is what guides the collection.

Abhijit Bhattacharya, recalling the twenty-year experience of the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Kolkata, in rescuing endangered archives and housing them in a safe space, points out that the process of selection is what determines the character of the archive. Criteria like budgets are doubtless important, but within institutional frameworks, an overall ideology is what guides the collection.

Individual private collectors at the meeting brought up a different set of issues. Bangalore-based Sunil Baboo, who has been a collector for three decades, talked about individuals who make substantial investments in collections. He flagged issues of insurance, of third party valuations, and a platform for private collectors to get information of collections. Shabbir Ahmed, a collector of coins and stamps, shared his passion for collecting books about his home-town Ahmednagar. He spoke of how his material was used – by school children to get a glimpse into history, as well as M.Phil and doctoral research scholars.

(Courtesy: Vikram Sampath, AIM)

Vikram Sampath, accomplished Carnatic music artiste and author of “My name is Gauhar Jaan” provided a captivating account of the music scene of the Subcontinent in the early 20th Century, where women artists, in the era of acoustic recording, had to thrust their heads into a large horn which would then create a gramophone record. Vikram, lamenting the lack of a “National Sound Archive” or any serious governmental effort in this arena, went on to set up the Archive of Indian Music. From sourcing and digitizing gramophone records, to cataloguing and dissemination, Vikram presented a forceful case for preserving the human voice as a valuable artefact.

Shabnam Virmani, director of the Kabir Project which has extensive archives of text, music and video around the 15th Century mystic poet, added to the discussion by wondering whether digitization of this music and easy availability on the Internet could be viewed as antithetical to the exclusive Guru-shishya parampara, or tradition of teacher and student that was an intrinsic part of the musical tradition itself.

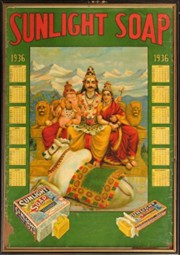

(Courtesy: Tasveer Ghar)

What is considered art, and what is dismissed as “popular culture”, can be very telling of a society’s aesthetic, as Yousuf Saeed, filmmaker and founder of Tasveer Ghar pointed out. Ephemera like social and performative life of images; the histories and everyday lives and voices of producers, disseminators and ‘consumers’ and various techniques of visuality/media of visualisation (for instance, ritual or theatrical performance, or political spectacle) are archived with careful curation and contextualization. Many of these are contained in Yousuf’s recently published book, “Muslim Devotional Art in India”.

The power of images was apparent in the film by Hri researcher Daljit Ami, “Conservation, Custodianship, Digitization” which juxtaposed preservation of Sikh heritage by the Panjab Digital Library, and the ritual “washing” and “cremation” of Sikh texts in a particular Gurudwara in Himachal Pradesh.

Dhaka-based photographer and activist Shahidul Alam jolted participants with unique insights into the visual image. Is it a photograph? Is it a painting? Is it art? Is it an advertisement? Alam spoke about the possibilities of the photograph as propaganda before the era of Photoshop manipulation, as well as photos of defining political moments.

Hands-on experiences of veteran archivists like G.Sundar, director of the Roja Muthiah Memorial Reference Library, provided insights into the painstaking tasks of rescuing damaged documents, and techniques of conservation and preservation in conditions of high humidity and low funding. Sundar described the life of the avid collector Roja Muthiah, who, having inhaled the highly toxic DDT used in those days to preserve documents, died young, leaving his immense personal collection, which was institutionalised in 1994. While archiving the vernacular, cataloguing in the language of the imprint is essential, else, difficulties arise in transliteration into Southasian languages. For instance, there are several Roman variants of the spelling of the collection of classic Tamil couplets: thirukural, tirukkural, thirukurral, tirukural etc. Setting standards of cataloguing in the vernacular is one of the tasks ahead. Sundar also pointed out the futility of indiscriminately digitizing and archiving the same information, rather than sharing efforts.

Father Ignatius Payyappilly a parish priest and the Director of the Catholic Art Museum of the Archdiocese of Ernakulam-Angamaly in Kerala, spoke of his work in rescuing and preserving palm leaves containing historical records of Christianity in Tamil Nadu and Kerala. A single palm leaf record of the mid-19th Century provides evidence of the practice of giving slaves as streedhanam (dowry), as well as recording the gift in front of witnesses.

Bhupendra Yadav, a historian with the Azim Premji University spoke as a consumer of archives, as well as an educationist. The “archive in education” reflects the expectation that people have from education: can it change fundamental social equalities, or does education merely reproduce elites?

Chintan Girish Modi is a researcher with Hri and part-time teacher at Shishuvan, in Mumbai, a cross between a traditional and alternate school. He spoke about exposing students to primary sources, currently being done through the “Matunga project”, which attempts to understand the locality in which the school is located. Chintan also shared his experiences of working through oral narratives through the Kabir Project and the Citizens Archive of Pakistan, where students are encouraged to examine diverse understandings of a singular narrative, rather than accept a single analysis handed down to them.

Lawrence Liang, co-founder of the Alternative Law Forum, Bangalore, flagged the need to achieve a balance between badly managed and run-down public archives which nevertheless allow public access, with private collections perhaps more efficient, but overlain with paranoia and secretiveness that hamper more democratic access. Laying out the current laws relating to copyright and intellectual property rights, as well as the principles of fair dealing and fair use, Liang pointed out that the world over – except in Southasia – archivists are leading the push for reform in copyright law, to increase public access. “Access and availability should be understood as broader than physical availability, and factors such as comparative costs taken on board,” he said.

Questions of the use of technology came up, with vehemently differing views – from putting everything online to restricting access. Rather than reinforcing this binary, however, what emerged was an appeal to examine questions such as archiving for what? Digitization for what, and access for whom? The question that must be asked is: for whom are you putting things online? With limited Internet access, is access only for the elite?

While the meeting itself was extremely energising, and provided, for the first time, a space for archivists in the region to meet each other, several possibilities for future collaboration arose. With the work of the Hri Institute having been presented by Sarita Manu and Kabita Parajuli, the possibility of Hri functioning as a facilitator was already on the table. The launch of an association of archivists at the regional level; more networking; collaborative exhibitions of archives; a joint campaign to reform copyright law in the countries of the region; sharing technical resources; standardizing databases; as well as organising a festival of films around the theme of archiving were some of the suggestions that will be considered in the coming days.

0 Comments